PDF Parsing: Using AI to turn (messy) climate policy documents into (readable) structured data

The ability to extract structured text from PDFs has haunted developers for 30 years.

PDFs were designed for creating and viewing flexibly formatted documents without the user having to worry about which device, operating system or browser they were using. This versatility revolutionised information sharing.

Yet the lack of formatting constraints made extracting structured information nearly impossible. As most climate-relevant law and policy documents are PDFs, this presents a challenge to our goal of making them fully searchable.

To a processing script, a PDF is just a stream of instructions for how to draw on a page: there are no paragraphs or words, only characters with variable properties (font, size, colour, etc) rendered at particular locations. Even worse, invisible characters are often mixed into the data for various purposes such as security. The image below shows a snippet of raw PDF data, to give you an idea.

Left with an amorphous soup of characters with no obvious or consistent semantic structure, what should we do?

Training computers to read climate policy documents

The first hint is that we humans don’t try to read byte code like the characters in the Matrix. Instead, we let third-party programs (such as internet browsers) render the relevant data and our brains figure out where the headings, paragraphs and figures are. What if we could get computers to do the same?

If that seems simple, it’s only because billions of years of natural selection underlie mammalian vision (a great example of Moravec’s paradox). But computer vision is catching up. In the last decade, humans have learned how to train models to “see” all sorts of things thanks to hardware (GPU) and software (CNN) advances.

For example, as shown in the image below, object detection models can recognise objects and their locations from raw pixel inputs.

An object detection model output (MTheiler, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Object detection models like this aren’t just good for typical images though. We can use them to recognise paragraphs, figures and tables too. The crux? We need tens of thousands of labelled examples to train a decent model.

Climate policy PDFs are messy and complex

Luckily, we’re not first to the party. A number of open-source models for exactly this task are freely available. As a starting point, we used Layoutparser’s PubLayNet*, a computer vision model trained on over 300,000 academic papers to recognise lists, headings, text blocks, tables and figures.

Applying PubLayNet to our database of over 3,000 documents gives reasonable results, but not good enough for the search quality we aspire to. The problem is that the PubLayNet model implicitly assumes pages conform to the structure of academic papers, which tend to show little variation and follow highly standardised formats. Academic papers usually have two columns of English text in a bland font, understated figures, and often no colour variation; documents in our database have variable numbers of columns with all sorts of fonts, colours and figures.

To get around this, we used a number of heuristics (hard-coded fixes). For example, when predicting different parts of a document (e.g. figures, tables, paragraphs, headings), in many cases PubLayNet would divide them into boxes that overlap. But text never overlaps, so we needed to find a way to automatically determine which boxes should take precedence. We’ll give you the nitty-gritty, but if you don’t fancy geeking out, skip the tech talk in the following section to find out what’s next.

Heuristics get messy too

PubLayNet gives metadata for each predicted box: coordinates, a type (title, text, list, etc), and a confidence score (e.g. 90% if the model is confident a box exists). A heuristic using this metadata might be: ‘If a “text” block is contained within a “list” block, remove the text block, provided the model is at least 10% more confident in the existence of the list than in the text. Otherwise, remove the list block’. The rationale is an empirical hierarchy (list blocks often fully contain overlapping text blocks, but not vice-versa), which should be respected unless the model is insufficiently confident that a list exists.

Despite their utility, heuristics like this quickly become unwieldy. This example alone contains many possibilities for both the hierarchical ordering of categories and the confidence value differences needed to override them. Ultimately then, selecting a high-performing set of heuristics requires lots of complicated code and empirical tweaking.

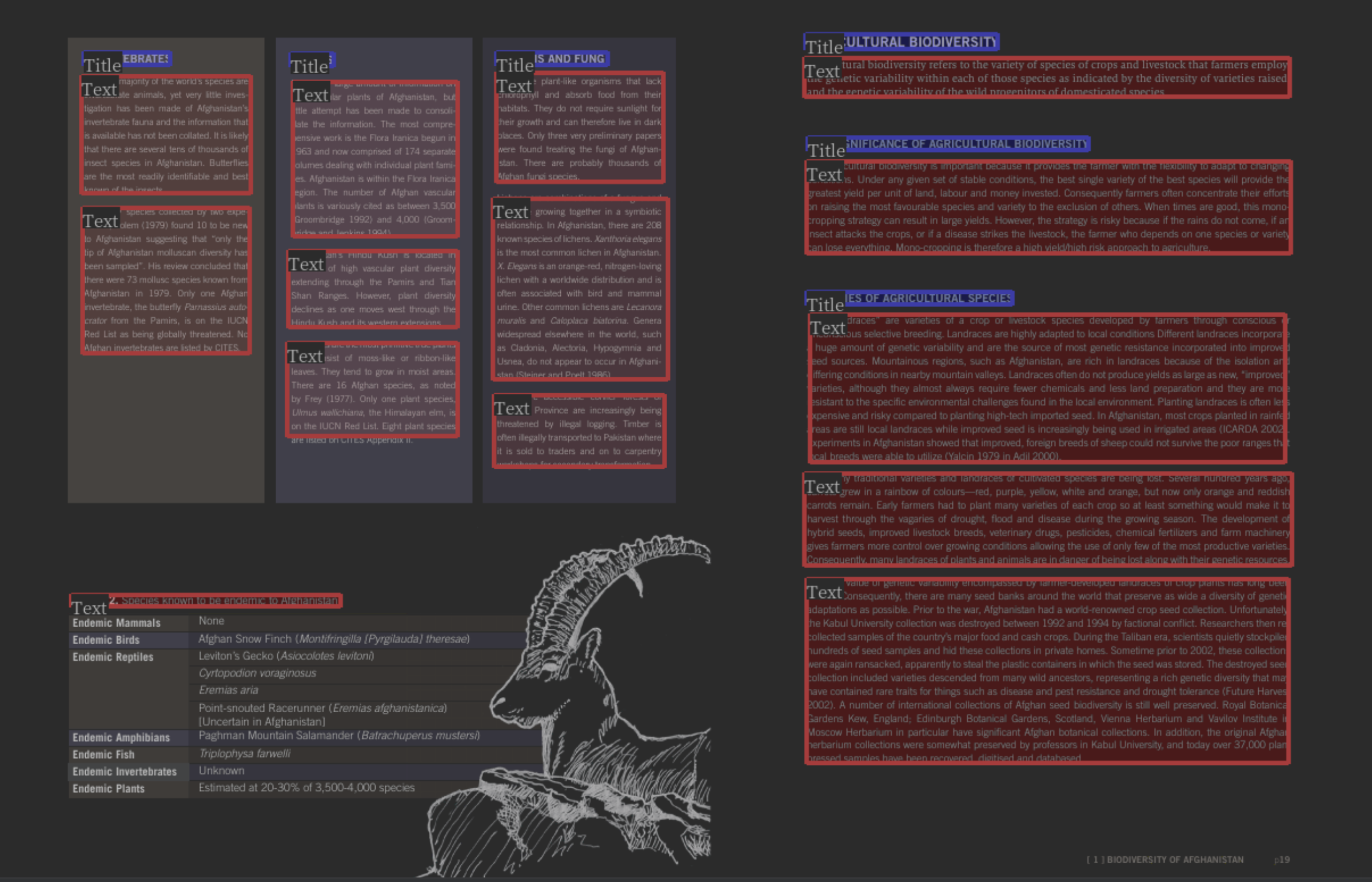

But our main reason for using computer vision is to avoid the complicated code we’d need to process raw PDFs! As such, we weren’t overzealous here: we only used heuristics to fix the most egregious issues and are working towards a less complex solution, which we’ll touch on below. For now, our current solution gives an accurate structure for most data: a set of images of blocks and their inferred types in the correct reading order. The image below shows a visual example of a structured documentoutput from our PDF parser.

But we’re not finished. The last step is converting these images to machine-encoded text instead of raw pixel values. Luckily, Optimal Character Recognition (OCR) on non-handwritten text is a very mature area of computer vision. We used Google Cloud Vision’s OCR API as it has high accuracy across all major languages. This is key for us: our previous approach to PDF parsing relied on third-party software for processing English language documents, meaning we couldn’t serve non-English speakers or documents written in other languages.

Leveraging computer vision for PDF parsing

Let’s step back. We’ve leveraged two computer vision techniques (document structure inference and OCR) to split documents into blocks of text. This is a necessary starting point for making documents in our database searchable using everyday (natural) language. You can read more about how we’re leveraging the latest language models to optimise natural language search on our blog.

What next? We already hinted that we want to further reduce dependence on heuristics, which have two downsides. First, heuristics require a lot of developer maintenance and become more opaque as more details are added. Second, heuristics are brittle: they fail when exposed to data that doesn’t conform to their underlying assumptions. To avoid these problems, we need to lean more on AI (machine learning) models over heuristics, following Andrej Karpathy’s vision for software 2.0.

Crucially, we don’t need to start from scratch: we have a working first version PDF parser that we can build on. The road ahead involves “fine-tuning” the models we’ve got - selecting examples of PDFs where our approach performs poorly, labelling these examples and re-training the model in an iterative path to better performance.

We’re optimistic about this and have already identified some easy wins. For example, we noticed that our models don’t detect headings if their font or colour is sufficiently different from those in academic papers, meaning our search tool might miss them. We can fix this by labelling more such examples.

Combining this iterative approach with a smaller, more maintainable set of heuristics, we’re confident we can develop a general-purpose solution to PDF processing that can be applied to any type of PDF document. The PDFs in our database are sufficiently diverse that our eventual solution will cover most people’s PDF parsing needs. This opens up an exciting potential for open sourcing in the future.

This is a big deal. There are trillions of PDFs out there, with no file format threatening to replace them. Automatic PDF processing has been needed for 30 years and will open up applications well beyond search, unlocking the potential for analysis of treasure troves of data in every field. Watch this space for where we take this with our own applications.

Call for collaboration

If you’re working on a similar problem, we’re keen to hear from you - tell us your tips, tricks and woes. We can solve problems faster by working together. Get in touch to collaborate or share your wisdom. You can also stay updated with our latest developments by signing up for our newsletter or following our ChangeLog.

*Technically, PubLayNet is the dataset used to fine-tune a pre-trained computer vision model, but we refer to the PubLayNet model throughout.